Cain and Abel: Why One Offering Was Accepted and the Other Rejected - Genesis Chapter 4

- Leisa Baysinger

- Jan 29

- 4 min read

A Hebraic Study of Genesis 4

Genesis 4:3–7

“And in the process of time it came to pass that Cain brought an offering of the fruit of the ground to the Lord. Abel also brought of the firstborn of his flock and of their fat. And the Lord respected Abel and his offering, but He did not respect Cain and his offering. So the Lord said to Cain, ‘Why are you angry? And why has your countenance fallen? If you do well, will you not be accepted? And if you do not do well, sin lies at the door. And its desire is for you, but you should rule over it.’” (NKJV)

These verses have been debated for millennia by both Jews and Christians. Exactly why was Cain’s offering not accepted and what does “its desire is for you, but you should rule over it”, mean?

Let’s take a look at these scriptures, laying the English aside, and peering into the Hebrew wording.

Cain’s offering and Abel’s offering stand as the first recorded acts of worship after Eden, and the contrast between them reveals the earliest pattern of how God is to be approached. Cain brought a minchah—a grain‑based gift offering. A minchah could express devotion, but from the beginning God’s pattern required that such a gift be joined to a blood sacrifice for atonement. So, if the olah - whole burnt offering for atonement (the oldest type of offering), was being offered here then Abel honored this pattern by bringing “the firstborn of his flock and their fat,” while Cain brought only produce. The issue was not that Cain brought grain; it was that he brought only grain, separating the gift from the atoning blood that made worship acceptable.

The phrase “in the process of time” (miqetz yamim) has prominent understanding in Scripture. Rabbinic commentators such as Rashi, Ibn Ezra, and Ramban interpret it as the end of a cycle—an appointed time of worship, a proto‑festival moment. At such appointed times, the pattern later codified in the Torah required blood + grain + wine. Abel brought the required blood; Cain brought only the grain. Abel’s offering aligned with the divine pattern; Cain’s did not. So, if it was a “festival or Sabbath type” offering that they were bringing, Cain’s offering still does not stand the test for what is acceptable as an offering to God according to His standards. Blood was required.

Although complicated in dissecting all the sacrificial guidelines, this pattern is later formalized in the Torah. Leviticus 1:3–4 and 2:1–2 show that the grain offering was never meant to stand alone in worship. Numbers 28–29 demonstrates that every daily, Sabbath, new moon, and festival offering included a minchah (grain offering) along with blood. Abel’s offering fits this pattern; Cain’s does not.

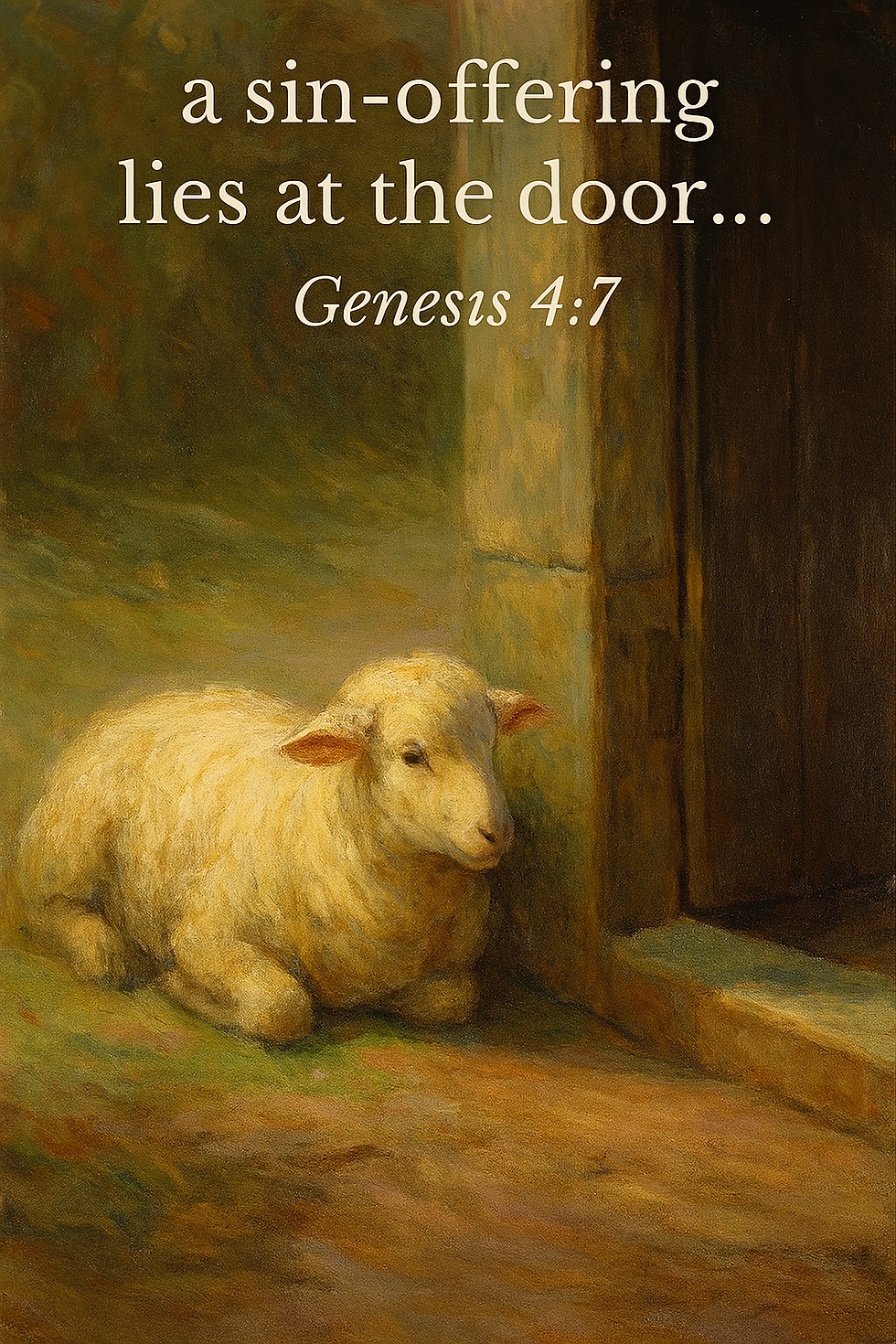

The Hebrew text of Genesis 4:7 deepens this picture. The word translated “sin” is ḥaṭṭā’ṯ, which can mean either “sin” or “sin‑offering.” The phrase “lies at the door” uses rovetz, meaning “crouches” or “lies down,” and petach, meaning “entrance” or “doorway.” Rabbinic tradition overwhelmingly reads this as a literal sacrificial animal lying at the entrance of Cain’s sheepfold. Rashi states plainly that “a sin‑offering is lying at your door—a lamb prepared for you.” Midrash Rabbah pictures the lamb waiting just outside Cain’s dwelling, ready to be taken and offered. God’s words were not condemnation but invitation: “If you do well, will you not be accepted? The lamb is waiting. Bring it, and your offering will be received.” This is a better translation of the scripture from a Hebraic perspective.

The second half of Genesis 4:7 adds another layer. The English phrase “its desire is for you, but you should rule over it” can also be read relationally: “His desire will be toward you, and you will rule over him.” The word teshuqah describes orientation or deference, and timshol describes rightful authority or rank. God was telling Cain that if he did what was right—if he brought the required offering—then Abel’s desire would be toward him, and Cain would retain his rightful place as firstborn. If he refused, the order would reverse. This interpretation fits the Hebrew grammar, the relational context, and the narrative pattern of Genesis, where obedience determines elevation and disobedience forfeits birthright. Abel becomes the accepted one; Cain becomes the rejected one. The younger rises above the older, just as later with Isaac over Ishmael, Jacob over Esau, Joseph over Reuben, Ephraim over Manasseh, and David over his brothers.

Cain’s tragedy is that he refused God’s gracious invitation. Cain wanted to do it his way! A way of rebellion! A lamb lay at his door, ready to be offered. God provided the means of atonement, but Cain would not bring it. His worship was self‑defined rather than God‑defined. Abel’s offering was accepted because it aligned with the divine pattern; Cain’s was rejected because it did not. The message is timeless: God provides the means of approach, but we must choose to come His way.

This message reaches into our worship today. God still calls His people to approach Him according to His way, not ours. The blood offering required is no longer the lamb lying at the door but the Lamb of God—Yeshua the Messiah—whose sacrifice fulfills and surpasses every earlier pattern. Just as Abel approached God through the shedding of blood, so we draw near through the atoning work of Yeshua, not through our own efforts, inventions, or self‑defined worship. The pattern remains unchanged: God provides the means of approach, but we must choose to come by the way He has appointed. Acceptance still flows from obedience, humility, and faith in the One whose blood speaks better things than that of Abel.

Blessings,

Leisa

Footnotes / References

1. Rashi on Genesis 4:7.

2. Midrash Rabbah, Genesis 22:7; 34:9.

3. Mishnah Menachot 1:1.

4. Babylonian Talmud, Menachot 76b.

5. Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Ma’aseh HaKorbanot 4:3.

6. Leviticus 1:3–4; 2:1–2; Numbers 28–29.

7. Ibn Ezra and Ramban on Genesis 4:3 and 4:7.

8. Hebrew lexical notes: ḥaṭṭā’ṯ, petach, rovetz, teshuqah, timshol.

Comments